Godfried Semel, although he made the small town of Monnickendam quite proud, was not too close to its citizens. Nothing but good food and where to find it interested him. Having no time for pettiness or small talk, he gave his opinions through the written word alone, on his website called Guzzling Godfried. For the rest he said little. At the age of eighty-something, gossip and town feuds did not interest him.

He lived with a stout Scottish Terrier named Dame in a small apartment with a doorman and big windows from which he watched the world go by. Dame’s soft feet rarely touched the ground and she ate little besides roasted chicken from Chez Lumière down the road, flavored generously with parsley, though on Thursdays she settled for harring, Hollandse Nieuwe, fresh from the North Sea. As for Godfried, his breakfast consisted of milk, eggs, cheese, vegetables, fruits and nuts so as to create a fertile foundation for his later-day indulgences.

For the most part Godfried Semel got his restaurant recommendations from his doorman, Herbert Rosendaal, who went by Happy, a short, bald man, with a worn smile, and the air of having spent his best years piloting the wealthy to the right locations. Whenever he did not have a recommendation at hand, he would flip through his Michelin guide with one licked finger, and look down his long nose at the small print just beneath his nostrils.

That day was a Tuesday, and a cold Tuesday at that. Winter had come early that year, the trees were leafless and there was a general barrenness that presaged more cold months to come. Because of the icy pavement, and Godfried’s bad hips and flat feet, neither dog nor man had ventured far in recent weeks. In fact, they had not gone further than Bistrot Berlage at the end of their street for four whole evenings, and that night would mark Godfried’s fifth.

“Good evening, Sir Semel. Good evening, Ma’am Dame.” Happy Rosendaal said. He had on a thick jacket, gloves and a red shawl though he spent most of his days indoors. In case of “tocht” (breezes, gusts of wind, drafts from opening and closing the front door), the leading cause of death in his family.

“Good day yourself, Rosendaal.”

“Off to Le Pont des Canaux?”

“Where? I can never understand a word you say. We are off to Bistrot Berlage.”

Happy was quite tall, and out of respect for Godfried, who was especially short, he kept his head on one side as he spoke, so he did not have to look down on him.

“If you don’t mind me asking, sir, but weren’t you invited to the Le Pont des Canaux’s secret opening this evening?”

“If I was, I would’ve received an invitation.”

“Oh, but you did! Just last week. Not that I was looking through your mail, I would never, but it just so happened to be on top of the pile…”

“Are you quite sure? I’d hate to go all that way for nothing.”

“I’m quite sure, Sir Semel. Absolutely positively sure. Sure, sure, sure. And anyway, you can’t take a lady to the same restaurant five times in a row.” He said, pointing at Dame.

“Calm yourself, Rosendaal. Le Pont des Canaux, you said? It would be good for my blog to go somewhere different. There’s only so much one can say about stamppot, and that’s all I can stomach at Berlage.”

“I’ll hail you a taxi right away, sir.”

“Well, alright then. I don’t see why not.”

“And, sir, if you see a certain Marjion Dijkstra, tell her I said hello. She’s waitressing tonight. Tell her “Happy Hans Rosendaal said hello”.”

“You talk too much.” Godfried told him.

When the taxi still had still not arrived after five minutes, Godfried decided to walk, Dame in one arm, walking stick in the other. There was not a cloud overhead; the moon, almost full, shone upon a light snow that had fallen earlier in the afternoon. The streets were deserted besides some young boys playing at being soldiers, and some girls playing top-spinning contests with small stones as prizes. The cold numbed his feet, but he kept walking until he reached a small building with curtained windows, dim light falling upon the blue-white snow like a yellow smudge, Le Pont des Canaux written in red letter about the entrance.

Deliberately, as if committing himself to something, Godfried stepped forward and walked down the path to the door.

Though a certain level of anonymity was required in Godfried’s line of work, he felt too old for disguises. He was also too old to pretend he did not like the recognition. The moment he entered he told the hostess: “Godfried Semel from Guzzling Godfried, at your service.” And followed her in.

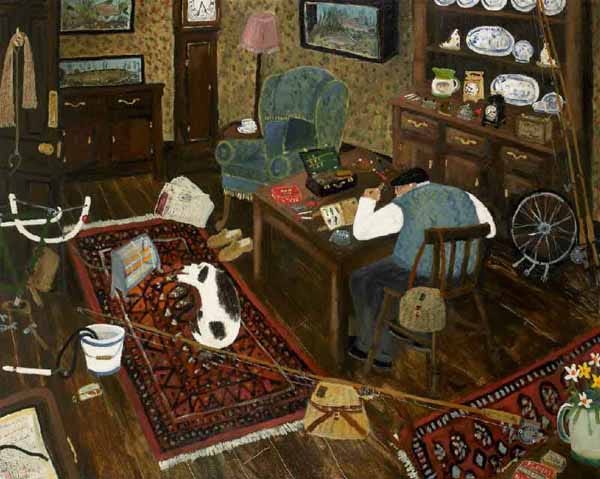

The restaurant was more agreeable than the outside would have led him to believe, furnished with a deep red carpet, many round wooden tables, comfortably traditional armchairs, and a rather large piano at which an elderly man with a suit and bow-tie played Beethoven. Everything was warm and cozy, or gezellig as the Dutch more aptly called it, and smelled of firewood.

The waitress asked about allergies and what he would drink. She was a large faced woman, round and rosy, quite perfect for the pan, Godfried thought, with two large blue eyes that bulged out at him, pug-like.

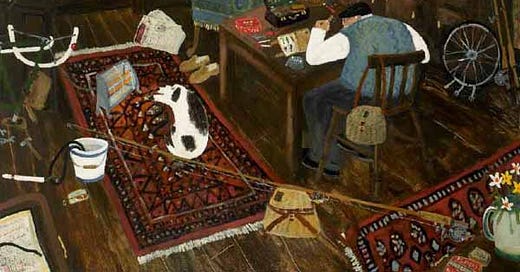

While waiting for his Pinot Noir he reached into his pocket and fished out his notebook and Montblanc writing-utensil alongside a meat knife, a butter knife, a small fork, a large fork, a soup spoon and a dessert spoon, all gifts from Jeroen Decker, a chef in Amsterdam he had helped win a Michelin star some ten years earlier. He leaned back and polished them lovingly with a piece of pink polishing cloth.

Soon the waitress was back with his wine, followed by a small bowl of something hot. Godfried leaned forward, anxious to smell as it was placed down before him.

“What an exquisite aroma! Chestnut soup with Gruyère crème?” Godfried’s nostrils were wide open to receive the scent, quivering and sniffing.

“Precisely right, Mr. Semel. With a dash of our very own parsley and freshly made croutons.”

Godfried ate slowly, savoring each bite, bringing his spoon down to Dame’s mouth every now and then for a lick. His palate was exquisitely sensitive, but Dame’s was superior. And though Godfried prided himself on his distinct ability to taste even the slightest hints of celery seed or paprika in the strongest onion soup, Dame wasn’t easily impressed. In truth, she bared her teeth at the soup.

“Warm and velvety, with rich, nutty sweetness balanced by a hint of earthiness — a cozy, forest-inspired comfort in a bowl.” He jotted down in his notebook. “7.23 out of ten. Needs more chest, less nut.” The important thing was that he understood what he meant.

The next dish was a vegetable ragout, followed by blue cheese fritters, the fourth a piquant pumpkin pie, the fifth a mushroom grilled on a bed of broccoli. Everything tasted rather delicious. He picked up his pen and briefly massaged his eyes, and sat for a moment with his elbows on the table and his head bent into his hands. 8.76 for the ragout, he decided, 8.242 for the fritters, 7.93 for the pumpkin pie, 8.431 for the broccoli. Very good, yes, yes. Not bad at all.

As soon as each meal was cleared up he was already licking his lips for the next, sniffing the air and speculating.

The sixth meal was called “the root of all evil”, a roasted, caramelized carrot which he rated his highest score yet, an 8.91, the seventh a cheese pastry so delicate and intricate Godfried needed Dame to pep talk him into breaking into it. 6.45. By the eighth course he thought he would close his eyes for a moment when the waitress returned carrying a large plate, much larger than the previous plates, on which lay a thick brown slab of something hot.

“Prime ribs!”

“Indeed, sir. This dish is called “Prime Suspect”, a prime rib platter presented with a side of intrigue.”

The waitress laid the plate before him and took a step back.

“Never in my life have I smelled anything as rich and wonderful as this. And I don’t say that often. Trust me, ask Dame.”

With his silver meat fork Godfried impaled a small piece of the meat and carried it up to his nose, then popped it into his mouth and began to chew slowly, his eyes half closed, his body tense. Delicious, easily an 8.96. Then the side of intrigue — mashed potatoes. Creamy, buttery, smooth, but there was something deeper to the flavor, Godfried caught that immediately. It tasted almost primal. He took another spoonful, then another. What was that added flavor? It lingered just outside the borders of his memory. Was it love, he wondered, or a mere fortuitous combination of delicious tastes? Whatever it was, it tasted magnificent. There was a feeling inside him of a hundred tiny bubbles rising up from his stomach and bursting merrily at the top of his head, like sparkling water.

“Servus, Servus!” He shouted. A little vellicating muscle twitched in the corner of his left eye.

“Is something the matter, sir?”

“I must speak to the chef immediately.”

“Is something not to your liking, sir?” The waitress’s eyes bulged with gentle imbecility.

“Not to my liking? Not to my liking? Quite the contrary! I have never tasted anything quite as magnificent. I must know what it is immediately.” From his pocket he extracted twenty gulden and waved it at her. “Go on.”

That seemed to do it. When she was sure no one had seen, she snatched away the money and slipped it in her server apron.

“Let me see what I can do, Mr. Semel.”

A few minutes later, she was back.

“Right this way.”

He found it difficult to stop himself from breaking into a run as he made his way after her through a long passageway where the wait staff took their break. Even through the smoke of their cigarettes he could smell the powerful odor of simmering meats clinging to the walls.

Godfried, who had expected the chef to be a man not a woman, raised his pretend hat, made a little bow, and handed her his card.

“We do apologize for bothering you,” he said, watching her face as she read his card. “But those potatoes. Not only were they mashed to absolute perfection, but there was an added hint of something that I cannot quite place. I must know what it was immediately.”

“That must have been intrigue.”

“Intrigue? Is that a type of herb?”

“If you think it is, then it’s probably not. Or perhaps it is.” She was grinning now, showing Godfried a set of enormous, ivory teeth.

“Please, I’m too old for riddles…”

“It’s not a riddle, it’s quite simple. If I tell you what it is, it’ll disappear. My apologies.” And she went back to cooking. She was a born chef, dextrous and quick, and handled her pans like a juggler. She could slice a single potato in twenty paper-thin slivers in less time than it took Godfried to wipe his nose.

“Just whisper it, then. I swear to the Holy Ghost and all that’s good that I won’t share it with a soul, not even Dame.” He pointed at his right ear and leaned forward.

“I don’t think you understand… If I tell you, it will disappear.” She threw his card in the dustbin and continued slicing her potatoes.

The problem, Godfried knew, was that he could not tell her precisely how he felt. He was only able to explain it in human terms, and what he felt was so much more than something definable by the five senses. Before he could ask about this so-called intrigue again he became aware of three pairs of eyes in his periphery. The sous chefs were staring at him, huddled together by the saucing station. The shortest was a stumpy man with a wide frog-mouth and spectacled eyes, the taller youth beside him had a wooden spatula held high in his gloved hand, and the third was midsized with a flat-face, practically snarling. Godfried turned slowly to look at them, his lower lip pushed outward, pouting like a spoiled child. He understood bright as day that were he to ask the chef again, they would throw him and Dame out of the kitchen head first.

“Very well then,” he said, retreating, “bring me another plate of the potatoes, will you please? I’ll try my best to decipher it myself.”

“Right away, Mr. Semel.” The chef said without turning.

Every evening from the opening night onward, at precisely seven-thirty (besides Monday when the restaurant was closed) Godfried Semel sat at the same table and ordered one Prime Suspect after another. He ate only the mashed potatoes and left the ribs for Dame and the happy wait staff who had already begun to grow fatter.

By that point Godfried had given up smoking altogether, for fear of harming his palate, and when he wrote his weekly posts on Guzzling Godfried he had developed the curious, rather droll habit of writing only about potatoes. At the beginning it had drawn many readers to his page in a quest to find the missing ingredient, but over time things had gotten quite out of hand. His latest tagline summed it up best: “Each spoonful draws me closer to the truth. They think they’re fooling me, but I know something devious is lurking in that creamy mound.”

One might think that, over time, Godfried’s fascination would dwindle. But it was quite the contrary. He dreamt, fantasized, lived for those potatoes. He awakened early each morning, shaking and shivering with excitement; only the potatoes could calm him down.

He never did find out the secret ingredient. Just a year after Le Pont des Canaux’s opening he died from a myocardial infarction on his way to the restaurant. They found him soon after, Dame squished underneath his spectacular stomach. Both were buried, one next to the other, in the Begraafplaats Monnickendam under large bouquets of potato flowers. His gravestone read: “Here lies one who never gave up.”

The chef, who felt at least partially responsible, had written him the chef's version of a bereavement letter: a recipe. And not just any recipe. All one needed was Russet potatoes, garlic, minced fine sea salt, butter, whole milk and cream cheese. Any idiot could have come up with it. In fact, at the opening of her restaurant a year earlier, she had made it quickly, in the spur of the moment, as a substitute for the charred brussel sprouts she had forgotten to buy.

Wow. Godfried. What a character. The “intrigue”. What a concept. Love how he rates to the thousandth decimal, HA! Sometimes the mystery of the thing becomes more important than the thing itself.

It’s so amazing how Substack allowed me to find one of my favorite writers (you)! This was such a great piece. So well thought out, and so funny.